The Sound of Sheet Metal – A Challenge

Categories: Blog, News, Articles Author: Felix Rohner 8th April 2016

The art of the metal sound sculptor resides above all in his ability to construct his sound sculpture as an intercommunicating system of energy stores. The complexity of these instruments also has consequences for their players.

The family of percussion instruments is the largest of all instrument families. One can find a wide variety of idiophones, membranophones, aerophones and string instruments, as well as many others which are difficult to classify. The Western world is not alone in having sought to classify the vast universe of musical instruments – Chinese and Indian cultures, among others, have also undertaken to sort and organize this field according to various criteria.

Today, globalization is in full swing. New instruments have appeared, and others are sure to follow. New points of view become possible, older ones silently disappear. However, let us hope that the world of making music together shall not fade away, and that human society is not drowned out by industrial, electronic music, or even silenced by the cry of war.

So hear the good news, brought by the metal sound sculptors: it shall go on!

Sheet metal instruments such as the steelpan and the Hang are sound sculptures of the modern era, with highly sensitive resonance bodies tuned to a defined pitch. These are hybrids, and don't fit neatly into the old categories.

These new instruments, which emerged in the 20th and 21st century, don't respond well to players who beat them if they are intended for making music together outside the context of the carnival. In Trinidadian steel bands, an art form integrating music of many cultures, the motto is: “Don't beat the pan – play it!”.

Playing by hand on a metallic shell is new and therefore requires a new art of playing by hand.

Percussion instruments are probably mankind's oldest instruments and can be found in all cultures. They can be used to create an infinite variety of sounds. It is therefore understandable that percussionists were the first to be drawn to the attractive resonance of these modeled steel sheets, and that their skillful demonstrations of virtuosity today fill the web.

We, tuners at PANArt, see ourselves as sound sculptors who, from our raw material – the sheet metal we call Pang – create sound sculptures that arise from the needs of our time. Classifying these makes no sense, as they spring forth anew each day, and are thus truly a work in progress. They should serve people and their music, as they can have the ability to attune a player's own life. How do sheet metal instruments such as the Hang, the Gubal, the Hang Urgu and the Hang Gudu manage this? What insights has our work with the hammer given us? Allow me to explain, as follows.

Proof was recently presented of the existence of gravitational waves, first predicted one hundred years ago by Einstein on the basis of his theory of relativity. Evidence was provided thanks to laser interferometry, a method of measurement capable of measuring very small differences of distance. This technique has given us, here at PANArt, many valuable insights into our work with sheet metal, including aforementioned views of these instruments.

Between 1988 and 2008, we worked with the physicists Thomas Rossing and Uwe Hansen, who had carried out research on the Trinidadian steelpan. The vibrational behavior of our sound sculptures was studied in detail by these two acousticians with holographic interferometry. With this method, the smallest oscillation amplitudes are detectable. The most important result of this joint research was understanding the complexity of the acoustic phenomena found in the steelpan and the Hang. Holographic interferometry gave us insight into the highly complex world of these instruments, the sound of which casts a spell on so many people.

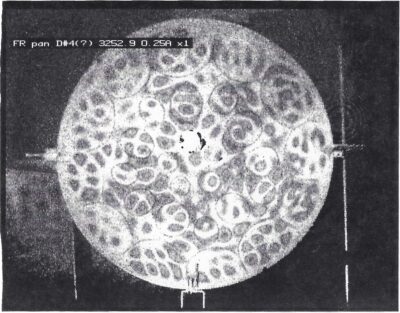

Here you can see an image of a PANArt Ping (a soprano pan), which has been stimulated with 3252.9 Hertz. Depending on the intensity and the location of the stimulation, the whole shell radiates sound. Beside it, we see the central tone field (Ding) of a Hang, with its five lowest vibrational modes.

One can easily imagine that these insights not only amazed us as tuners, but also commanded our respect. What a wondrous art were we practicing! This went beyond our understanding. It was truly mystical. We were giving order to a cosmos. This was not just tuning notes. It was tuning a multitude of stores, allowing them to exchange energy. It was about storing energy by means of a geometry that reflects bending waves or also lets them pass, thus giving rise to an interplay with other stores (oscillating modes).

Such an instrument – this was now clear – could not be mastered by the player. Each stimulation gave rise to a new sound. Not one of these sounds could be replicated exactly. This was not therefore an instrument that could be mastered in the conventional sense. These were not simply notes, or tones being played, but here was a wealth of colors, an iridescent occurrence, an oscillating, enchanting cosmos.

These findings were deepened by our encounter with Professor Anthony Achong. This physicist, then working at the University of the West Indies (UWI) and organizer of the International Conference on the Science and Technology of the steelpan (ICSTS 2000) opened our eyes to the art of tuning. His investigations demonstrate how the master tuners of the steelpan are able to reshape the iron sheet by continuous hammering in a way that the introduced stresses create – by means of modulation of the partial tones – a sound dynamic called the “sweet sound of steel”. The metallic chaos is tamed in an appealing way – “beautiful pan”.

As tuners, we had taken a giant step in the understanding of our work. There was no longer any doubt: the player could no longer see the instrument as separate from himself, but on the contrary as an extension of his own body. This new perspective inspired our work. It was now our task to study the essence of hearing and the functioning of our senses.

Our study of hearing and harkening led us through the literature concerning the physiology of the ear, through books about the Tomatis Method, to prenatal psychology, and to hypnosis. Deeper study of human sensory perception further amazed us. The surface of the hand, with its sensors for pressure, vibration, pain and temperature, appeared as a highly sensitive part of our body.

It was now clear that playing on the stiff, prestressed playing surface of Pang required an awareness that two highly sensitive worlds were meeting. Here the human hand, and there the curved highly stressed playing surface. The Hang was thus a resonance body to be met with respect, and certainly not a drum to be beaten.

We developed a new culture of the dance of the hands, taking into account how the player's energy is transferred to the playing surface. Like the tabla player, whose hands are always in contact with the tensioned membrane, Hang players should likewise remain in contact with the resonance body so as not to produce arbitrary, chaotic sounds that could harm their ears. A culture of measure is required. These insights appeared in print in the Hang Guide of 2010.

Like a mirror, the Hang gives the player an immediate answer, and these direct responses act like a seismograph, an amplifier, a catalyst. Something happens to the player's consciousness: boundaries dissolve, the sound cannot be spatially located. Player and listener merge into the great oneness. This phenomenon is expressed in thousands of letters to PANArt.

As it became clear that the Hang could not be a hang drum, tensions grew between PANArt's tuners and those who had been playing the Hang as a drum. Going against advice to seek out a complex way of playing, in which the player's hands remain in as steady contact as possible with the magical sphere (as if in a dance with a partner), they played the Hang as a percussion instrument, trying to combine rhythmic patterns with melodies, their hands usually positioned high above the playing surface. Their playing was characterized by a flow of sequences of patterns that often culminated in the effort to capture the music, even in notation. The complex acoustic body was not dealt with fairly, and the sounds that reached the ear were often distorted.

Due to a high demand for Hanghang, many copies appeared on the market, in early days mostly produced by former steelpan makers. As these were bought mostly by players interested in percussion, pressure rose to give these new “percussion instruments” a name.

US steelpan maker Kyle Cox from Pantheon Steel brought the term “handpan” to the scene, as the name Hang was registered as a trademark by PANArt and couldn't serve as a generic descriptive term. That PANArt refused to accept the term “hang drum” subsequently proved useful. While we, the makers of the Hang, understood our creation as a sound sculpture, the term handpan, originating in the USA, prevailed and spread quickly despite resistance by some builders of Hang instrument replicas. PANArt never referred to the Hang as a handpan, since their creation had clearly stepped away from Trinidadian steelpans in terms of material, form, way of being played, as well as sound. The new term subsequently led to misunderstandings.

The situation in the field of sheet metal instruments can now approximately be described as follows: Trinidad, the Mecca of steelpans, is not interested in handpans. The steelband culture of the Caribbean island has enough to do by itself.

In the year 2000, PANArt's tuners, along with their newly-developed Hang and other Pang instruments, were invited to the International Conference on the Science and Technology of the Steelpan (ICSTS 2000), in Trinidad. The Hang resounded, and was greeted warmly. “This is not our culture” was a statement frequently heard, and so we could return home peacefully. In the land where collective playing of steelpans with sticks predominates, playing by hand was seen as somewhat odd.

The euphoria surrounding steel bands in Europe and America has faded, for many reasons. The steelpan eludes standardization, and the sound of steel bands may have been over-exploited. As an element in various musical styles the once exotic sound may find its place again – either as produced by an actual instrument or as a synthetic sample.

As well as this, a passing of the hype surrounding the making of handpans (about 100 replicas of the Hang) is foreseeable. Unpleasant developments have dampened enthusiasm in recent years: rapidly-made instruments have been sold at high prices to inexperienced buyers. Furthermore, a plethora of available scales have contributed to a confusing picture.

Truly new developments can't be identified, unless one wants to mention the Oval from Barcelona, a Hang-shaped midi controller made of white plastic. Given the most important trait of metal sound sculptures – their strong non-linear behavior – this is, to put it mildly, a feeble crutch. Only the exterior aspect of the Hang's casing has been copied, and arbitrary sounds installed electronically. The Hang's generous invitation to develop a tactile culture, in direct contact with the instrument is completely ignored.

In Trinidad, incidentally, a midi controller was developed in the form of a steelpan several years ago: the PHI (Percussive Harmonic Instrument), where plastic sensors are struck with sticks. A similar instrument, the E-Pan, comes from Canada.

The slit drums shaped like a Hang or a curling stone cannot be considered as further developments, and have nothing to do with the art of tuning metal sound sculptures. Unfortunately, these are often marketed as handpans or presented as an alternative to the Hang. Unlike the prestressed tone fields of the steelpan and the Hang, the sawed tongues don't produce pulsed sounds and have a very long sustain. Their inharmonic sound spectrum is unfavorable. Musically, to be used effectively, the tongues need to be damped. The corresponding damping technique can be found in the Indonesian Gamelan orchestra.

The constraint to tune metal sound sculptures with tone systems in equal temperament impedes, in my point of view, further developments that achieve higher levels of quality, where these instruments could express their therapeutic or even medical effect.

If one considers the metal sound sculpture holistically, as we tuners at PANArt do, then one sees traditional tone systems such as scales as a restraint on artistic freedom. We therefore plead that no more constraints – originating from a hammer or a machine – be imposed, but that human perception, as well as the laws of physics, be our guides.

An appropriation of the instrument by certain cultures is thus avoided, and the individual is able to find a fresh approach to music. Sheet metal instruments are no substitute for traditional instruments – they have their own characteristics which require a high level of attention as the player ventures into musical terra incognita.

The rapid spread of information as well as high demand for instruments has put the sound sculptor under pressure to produce more, and faster. But simply pressing a tone field into a resonance shell is not all it takes! At the heart of the integral art of tuning is the tuner's work with the hammer, shaping the energy stores of his sound sculpture hammer blow by hammer blow. Without this work, results are rapidly built, banal instruments. Their appeal wears out in a little while. These exhausted second-hand instruments are then put back on sale online again.

That criminal activity has spread to this family of instruments should give us pause for thought. Parallels to drug trafficking are unmistakable. The Hang, particularly, is being abused in a troubling way. People lose a lot of money or get broken instruments. Sound sculptures by PANArt, retuned and modified by other tuners, are sold as a Hang. A lack of clarity about the new instruments' quality criteria predominates amongst buyers.

With the Gubal, the Hang Gudu, and the Hang Urgu, as well as the three string instruments the Pang Sei, Pang Sai, and Pang Sui, PANArt has ventured into new musical territory. Here, music is not seen as a performance, but – as with the Hang – as praise to being.

The Pangensemble is a whole in which the individual embeds himself and communicates with the others in a musical language. The Pang player knows that the instrument is speaking to him, and is not handled as an object. Otherwise, the ego is all too easily inflated, measure is lost, and Carnival prevails...